|

MARY PICKFORD:

Mary Pickford was so popoular that she inspired

paper dolls . . .

Mary Pickford Paper Doll

Mary Pickford begins to talk, with clips not only

from her movie, Coquette, but scenes from her only movie with husband Douglas Fairbanks, Taming of

the Shrew (1929). Narrated by Whoopi Goldberg:

Mary dances in Kiki (1931):

Poor Little Rich Girl - 1917 -

Secrets, with Leslie

Howard, 1933, Mary Pickford's last movie:

There is a lot more to this movie so stay

tuned to see if Maven can find the rest of it!

Maven has come across a link to being able to watch

Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks in their only cinematic appearance in The Taming of the Shrew (1929)!

Just click on http://video.tiscali.it/canali/truveo/4261623522.html! for 65 minutes of sheer fun! Is it the best copy?! No, but it's free!

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS:

Douglas Fairbanks Documentary:

IRON MASK (1929 - 1952) -

This is a Douglas Fairbanks movie . . . the 1929 version is as delightful as only Doug, Sr., could make it but with an added

twist: It's released again in 1952 with Doug, Jr., doing the naration. Some scenes are difficult to watch with

very light patches but still worth watching.:

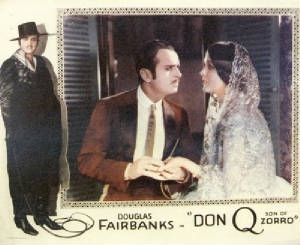

| Mary Astor and Douglas Fairbanks |

|

| In "Don Q, Son of Zorro" (1925) |

Mary Astor wrote about makeup during the twenties

when she was co-starring in her 1925 movie, Don Q, with Douglas Fairbanks. Maven isn't sure they were paid

enough to go through this stuff!

Mary Astor on Makeup in the Silent Era

THE FIRST SUPERSTAR COUPLE

Much of the lives of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks can be seen through the home - the lodge - that Fairbanks bought

and then gave to Pickford as a wedding present: ARCHITECTURE IN HOLLYWOOD: Pickfair

Ironically, the original

building that was described as a "hunting lodge" that became Pickfair lather spawned the "Pickfair Lodge."

Pickfair Lodge was built

on the corner of the Pickfair estate for Buddy Rogers after Mary Pickford died.

"Pickfair

Lodge was a home built on a corner of the Pickfair grounds by Buddy Rogers after the death of Mary Pickford. This small but

beautiful mansion housed many of Mary’s keepsakes until 2003, when it too went on the market. Some of its features recalled

the original Pickfair, including a western bar that Buddy had fashioned from the old Pickfair bomb shelter, which was on the

Pickfair Lodge section of the property."

This is from http://www.marypickford.com/faqs.html and errs. Pickford had the western bar installed

off the port cochere of Pickfair as a Christmas present for her then husbland, Fairbanks.

Just don't ask Maven where

they got the idea there was a bomb shelter on the grounds because this is the first she's heard about it!

That sounds

more like the misinformation that has come out of Pickfair since Meshulam Riklis and his wife, Pia Zadora,

bought the house. They torn down most of Pickfair "because of termites."

Some termites since this was the first

anybody seems to have heard about them.

Many

people today think that the Pickfair they see is the original home of Fairbanks and Pickford.

Trust Maven . . . it ain't!

Hollywood to Paris

Mary Pickford's Own Story

of Her Trip Abroad with Douglas Fairbanks

by Mary Pickford

Hollywood to Paris is copyrighted © by the Mary Pickford Foundation

and reprinted with the permission of the Mary Pickford Library.

Chapter I

There were three reasons why I didn't want to go to Europe. First, my fur coat was in California; second, I wanted a rocking

chair vacation - and I mean this literally, for the ambition of my life at that moment was to slip unobtrusively away to a

cool, secluded veranda, find a rocking chair and sit there for two whole months. The third reason was that if I went to Europe,

I couldn't say goodbye to my mother, for she was in California and I, at the time, was in New York. But the wanderlust was

upon Douglas and once he sets his mind to a purpose, well - he sets.

He quickly overruled my objections by fulfilling them. Before I could get my breath, he had ordered a new fur coat for

me, had wired an invitation to Mother to accompany us on the trip, and, most absurd of all, had agreed to buy a rocking chair

and carry it all over Europe on his back if necessary so I could sit down whenever the impulse seized me. It was useless to

oppose him. He was simply irresistible, and I was quickly swept off my feet by his enthusiasm.

But I am getting ahead of the story. Let us go back for a moment and tell how it all came about.

We were nearing the completion of Little Lord Fauntleroy [1921] [photos] after sixteen weeks of hard work and I was physically and mentally exhausted. Playing the dual role - the part of Fauntleroy

and also Dearest, his mother - had been a very trying task, because it called for so many double exposures - those scenes

which flash by in seven seconds on the screen and require fourteen to eighteen hours of continuous work to make.

I felt as though I never wanted to hear the click of a camera again or see the inside of a studio. In fact, I was once

more in the mood to retire. I retire periodically, you know - after the completion of every picture! It's quite a joke around

the studio.

Douglas was going to New York for the opening of The Three Musketeers [1921], and, of course, he wanted me to go with him. This necessitated our working day and night in order to finish

the actual photographing of Fauntleroy so we would be ready by the time Douglas had completed titling and editing his picture.

When the time came to leave, I took my brother, Jack, and Al Green, who had co-directed Little Lord Fauntleroy, and we wrote most of the titles on the train and completed

the assembling of the film in New York, often working all day and until two and three o'clock the next morning.

This is one of the hardest phases of our work, for it comes at a time when we are tired in mind and body, when the very

thought of the characters has become wearisome. In spite of this, however, we are forced to go back over the ground again

and try to work from a new angle - that of seeing this picture through the eyes of the audience.

In New York, we registered at the Ritz-Carlton, but we really lived with Little Lord Fauntleroy and his mother in a tiny

cutting-room at the United Artists office, where the work of putting the picture together was carried on.

Of course the premier of Douglas' picture came before mine, but I am not going to say very much about that as he plans

to tell the story himself in the article which follows this one. However, I was a very interested spectator at that first

night performance, and very proud of Douglas as I knew better than anyone else how he slaved to make The Musketeers

a success.

Douglas had been so wrapped up in his story, so absorbed in watching the work of every player during the four months the

production was in the making, that he had actually shed his own personality and taken on the personalities of the characters

in the film. One night I would have as a dinner companion the agile and dashing D'Artagnan, clanking spurs and all; the next

evening it would be Athos, Porthos and Aramis, and then the haughty Louis XIII, or the austere and crafty Richileu. Never,

it seemed, did I have Douglas Fairbanks.

One night when it seemed the kingly Louis was dining with me, I was so impressed with the dignity of his bearing that I

began to imagine myself one of the ladies of that ancient court and when he rose I found myself rising too. This was too much,

so I threatened to eat in the breakfast room with Fauntleroy and Dearest if Douglas didn't stop bringing his characters home

at night.

Sometimes we worked so late at the studios that we would come home in our make-ups and our household became quite accustomed

to seeing Fauntleroy come bounding up the stairs, followed by D'Artagnan in all his plumed glory. And when we had company

I used to wrap D'Artagnan's velvet cape around me in deference to my guests and it made quite a respectable train.

I hope you will forgive me for the way I am telling this story - I seem to skip around so. But there are so many things

that had a bearing on our trip abroad.

In all probability we never would have gone if it hadn't been for Charlie Chaplin who was in New York at the same time we were. In fact, he was staying at the same hotel. Douglas has promised to tell you

why he was there, so I won't spoil his story.

Of course, Charlie was very much interested in Fauntleroy and The Musketeers and offered to do all he

could to help us with the editing. Right here I want to say, though, that we show our pictured to Charlie with fear and trembling

as he wants to cut everything out and insists that shots should be taken oer when players have beem dismissed and sets torn

down. I must say, however, that I have learned on thing: Never argue with Charlie. Whatever he says, agree with him. If he

insists that black is white, admit it is so, otherwise you will be arguing all night. He went to the theater with us and saw

the picture run the afternoon before the opening, when we were rehearsing the music. What a beehive of activity that place

was - everybody rushing madly around, doing the million and one things that always come up at the last minute.

Charlie found at least five places in the picture which he thought ought to be cut; the fight in front of the Luxembourg

ran too long; there was too much of the scene where D'Artagnan asks Buckingham for the jewels; and there were many other glaring

faults. We were sitting in the back of the darkened house, and every time Douglas dashed down front to suggest diplomatically

to the orchestra leader that he leave out a few bars that didn't seem quite suitable, Charlie would say to me, "Mary, that

scene must come out, it will ruin the picture. Whatever you do, don't let Douglas run it that way. Take your scissors and

go right up into the projection room and see that it is taken out."

But that night, when the audience was hushed and tense, Charlie sat forward in his chair, gripping the rail of the box

with every muscle pulled taut under the spell of the picture. And once he fell out of his chair. He had sat so far forward

and tipped the chair up so far in back that it finally slid out from under him. When the pandemonium of the audience was at

its height at the end of the first duel, Charlie put his fingers in his mouth, boy-fashion, and whistled so shrilly that it

hurt my ears. In fact, I looked around to see where this terrible noise came from, and was astounded to find that it was the

dignified Charles Spencer Chaplin. And when the show was over, he was generous enough to admit that he had been entirely mistaken

about the cuts - that in his judgment the film was perfect.

The showing of my own picture was, in a way, a repetition of the intitial presentation of The Three Musketeers.

There were the crowds, for which I was very grateful, the thrill that comes to one from a responsive audience, the music,

and the dramatic critics - bringing with them just that slight dread one feels at wondering what they will say.

And what a mad rush it had been all that day to get the picture ready. We had gone to bed at two o'clock that morning and

were up again at eight, back at the grind of cutting, trying to make the picture run smoothly and at the same time have its

full dramatic power.

The fact that we had come on from the coast with an uncompleted picture made our work doubly hard, for we were working

without any of the advantage of studio facilities. The telegraph wires were kept hot between New York and Los Angeles with

queries, instructions and matters bearing either on the titling or the cutting. One telegram we sent was three hundred words

long, containing a full working title sheet.

Add to this was the rush of making final arrangements at the theater. The music score had to be synchronized with the picture,

which required a tedious rehearsal. And of course there was the mass of small details, each requiring personal attention.

My greatest problem seemed to rest in being in two places at one time - the theater and our apartment at the Ritz. Our stays

in New York are always so short and there are so many things to be crowded into such a brief space that our rooms resound

with a regular bedlam. It is one wild jumble of newspaper men, arriving packages, waiters, promoters, old time friends, applicants

for jobs, shoe clerks, businessmen, mothers with little daughters they wanted to start on the road to film fame, lawyers,

street car conductors with scenarios, clergymen, prize fighters, telegrams and messenger boys. And it is not strange that

on the day of the opening, this turmoil should have been at its height.

Shortly before six o'clock Douglas dragged me away from the theater by sheer force. "This won't do," he said. "You have

got to get some rest." I knew it would be useless to remonstrate, and beside I was dead tired, so I got meekly into the car

and said not a word until we arrived at the hotel. As soon as we arrived, my secretary asked if I had written my speech for

that evening.

"Speech? - good gracious, I forgot all about it!"

Imagine the chaos of thoughts that went tumbling through my mind. The biggest picture of my career about to be shown, and

no speech prepared. What was I to do? I was so tired that it was absolutely necessary that I lie down to keep from going to

sleep on my feet. Douglas consoled me finally with, "Never mind, dear, you rest and I'll write the speech."

When he brought it to me later, I was horrified to discover that it was two pages long! However, I knew how hard he had

worked and how anxious he was to help, so I didn't want to risk offending him by complaining about the length. I put the speech

on my dressing table and tried to memorize it as I dressed. To my great surprise and satisfaction, I got along very well indeed.

In fact, when we left the apartment for the car, I was quite sure that I knew every line of it. But when we got to the theater

I was so overwhelmed by the crowd, by the fact that it was my first appearance as a producer, and so upset by the small mishaps

which occurred (for instance, the film broke three times) that I completely forgot my speech.

Well, then I just told the audience the facts - that every time I get up with a prepared speech I forget it; that it was

my first appearance as a producer; and that they had all been very kind and generous in their reception of the picture; that

whatever merit it had was due not to my own efforts alone, but to the fine cooperation and support of our organization. Then

I finished by saying I was too excited to make a speech anyway and sat down.

The thing that Charlie Chaplin had come to New York for had been worrying Douglas for sometime. Of course he didn't know

that I suspected this, but I had watched his face closely a time or two. So I wasn't surprised when he said on our way back

to the hotel that night, "Well, the pictures are started now, let's hope they'll succeed, and let's take our vacation. We

both need it as a let-down from the pace at which we've been traveling."

Chapter II

Hollywood to Paris is copyrighted © by the Mary Pickford Foundation

and reprinted with the permission of the Mary Pickford Library.

Copyright © 2001, Diane MacIntyre, The Silents Majority On-Line Journal of Silent Film, at silentsmajority@visto.com. All rights reserved.

Hollywood to Paris is copyrighted © by the Mary Pickford Foundation

and reprinted with the permission of the Mary Pickford Library.

Chapter II

(The narrative is taken up at this point by Douglas Fairbanks.)

Were you ever - by any chance - caught in mid-ocean, hanging on the edge of a raft, no vessel in sight and a threaening

storm approaching? If you were, you know by experience how one feels who goes to see his own picture shown on its first night.

You glance around and try to figure to a mathematical certainty just what your chances are of really interesting the critical

and jaded boulevardier.

Well-defined emotions usually run in their given channels during the production of a picture, but upon its completion,

I should imagine one's mental chamber rather resembles a kaleidoscope. Your dominant feeling is one of utter hopelessness.

All your healthy optimism has taken flight. You are eager to find looks of approval, but when you do, you pass them up and

grab on to the grouchy individual turning your way whose manner may be the result of a torpid liver.

All things considered, the first night of The Three Musketeers [1921] decided my fate. I did not commit suicide. I felt that the thing might have a possible future, but I determined

to wait at least a year and a half to find out whether the generous approval given by the first night audience was genuine

or merely friendly.

Mary and I are frequently asked how we feel about the receptions we receive - I mean personally and apart from our work

- on such occasions as the opening nights of Little Lord Fauntleroy [1921] [photos] and The Three Mustekeers and while we are journeying. When I am questioned I never can help recalling an incident

that occurred while we were driving in Tunis. I saw an enormous mob. I just naturally resented it because up to that time

we had been the center of attraction and of mobs. I was immediately curious to know who had the right to call out a number

of people like that. So I stopped the car and pushed and shove my way through the center of this shifting and surging mass

and found - what do you think? An elephant! If you can draw from this parallel what I mean, you will understand that we do

not take too serously nor think too much of this peculiar condition that has arisen out of the popularity of the film favorite.

The following day - the picture was first shown on Sunday evening - I returned to the theater at both the afternoon and

evening performances. For while the reviews in the newspapers could not have been better, I was anxious to see what was happening

at the box office. Both performances were a "sell out" with the result that I was up early Tuesday morning feeling like a

two-year-old.

That dear old genius, Charlie Chaplin - and I say genius advisedly - a man born of tragedy, with an understanding of life and a love of things beautiful a man

whose reflections are clear and distinct - dear old lovable Charlie was sailing for Europe. So Mary and I went to Pier 35,

North River, to bid him bon voyage.

When we arrived at the Olympic, the boat on which we crossed before - and a wonderful way to get from this side to the

other and vice versa - from some mysterious and unknown place in the offing a still small voice whispered in my mental ear:

"How would you like a trip to Europe?" My more sensible self, bent on keeping me properly at work, throttled the voice

for the time being.

We disentangled Charlie from the newspaper men and friends who were surrounding him and said goodbye. Charlie has a habit

of taking things very serously - or otherwise. On this occasion he was so tragic that I rather expected him to say: "I regret

that I have only life to give the Atlantic." Really he used up - at a fair estimate - about ten thousand dollars worth of

emotion at the rate his emotions register on the screen.

"Well, goodbye, Charlie!" "All aboard!" "All ashore!" And as the boat pulled out the still small voice at my mental ear

seemed to have gathered volume as it said again: "How would you like to go to Europe?"

I repeated the whisper to Mary, who, in effect, dragged my by my physical ear into the waiting taxicab and said: "Nonsense,

we have too much work to do."

But persistency is the mother of ocean travel. At any rate, in this case it resulted ingetting out the little old steamer

rugs, for Mary finally succumbed.

Once you hit upon the idea of traveling you unconsciously begin to map, to plan, to think and to arrange. I always figured

that traveling is a science and an art. Because of the conditions under which we had lived for the last year, strenuous, terrifically

active, I realized that the first part of our trip must be in the same tempo, else the let-down would be too violent. We must

constantly feed the eye in order to divert our thoughts from the thing last in hand. The successful traveler must make himself

wax to receive impressions - putty to be moulded by the new environment.

There is a type of traveler who makes himself rigid against every new sensation. In whatever land he finds himself, he

regards the other fellow as the foreigner and preserves throughout a sort of I-am-better-than-thou or difference-from-me-is-the-measure-of-absurdity

attitude. If you are too prejudiced, too positive, too decided about everything you will lose half the values that you come

in contact with. The more methodical traveler may think the rapid covering of ground is a waste, but this is not the case,

for, all the while that you are making your bird's eye survey, the quiet little observer in the back part of your mind is

busy ticketing and cataloging all the worth-while things and preparing an itinerary that will bring you back to spend days

in getting properly acquainted with - say - a tiny miniature in a corner of the Louvre. It takes time to make yourself sufficiently

receptive to make a perfect print of the very fine and excellent things Europe has to offer.

And so in less time than it takes to tell it, Mary and I mapped out our trip abroad - in our minds at least. We would get

in our car and motor South. Our plans would call for no plans. We would go wherever and whenever the spirit moved us - to

Switzerland - to Italy - and to Africa. Yes, we would visit Africa. It would be a great adventure.

On our return to the hotel we got out the hotel atlas and I showed Mary how we could cross from Naples to Sicily and to

Tunis. We became so enthused over our African adventure that we both forgot important appointments with our lawyers. I was

as excited about the trip as a school boy, especially the African part of it. Tunis with its Arabs and dancing girls, the

ruins of Carthage and Biskra, on the edge of the Great Sahara Desert, stimulated my imagination. My enthusiasm must have been

contagious for very soon Mary could talk of nothing else.

Naturally there were many things to be done before we could leave, getting our accommodations on the Olympic was the smallest

detail. By a stroke of good luck we got the same suite in "B" deck that we had the year before. If Mary and I had been traveling

alone there would not have been so much to do, but we started out like a party on a Cook's tour.

In the midst of these preparations Mary and I went up to Boston for the opening in the Hub. I think our three days there

were as crowded with incidents as any we ever spent anywhere. I lived on coffee and handshakes. I'm sure Boston has a million

inhabitants for I shook hands with every one of them.

Because of the reception of The Three Musketeers at the Lyric Theatre, it was decided to advance the first showing

of Little Lord Fauntleroy and put it into the Apollo Theatre, almost next door. It was a brilliant idea for it enabled

Mary to witness the first New York showing of her picture before leaving for Europe.

Was had another wonderful "first night." Everybody in the film world in the East attended the opening and the picture scored

a huge success. Its enthusiastic reception naturally took a load froom Mary's mind and for the first time in many, many months

we were free from worries and ready for a holiday.

Our sailing day arrived almost before we knew it, but everything was in readiness and with light hearts we boarded the

Olympic shortly before she was nosed out from her pier. Sir Bertram personally welcomed us aboard and we were overwhelmed

by the attentions of the officers and crew. Our suite was a veritable bower of flowers and there were enough baskets of fruit

to have started a good-sized shop.

There were ever so many people we knew in the passenger list and one of them, a brother Lamb, came to me with a story how

he succeeded in getting a cabin all to himself. It seems he was assigned to share a cabin with an Englishman - a total stranger.

This Englishman in the hope of keeping the cabin for himself exclusively, informed the other that he suffered terribly from

asthma and would, therefore, ruin his chances of getting any sleep on the way across. "I don't mind a little thing like asthma,"

replied the American, who was alive to the game. "As a matter of fact, I am suffering terribly with leprosy."

Needless to say he won the cabin for himself.

At last, with the blowing of many whistles, the great ship backed out into North River, and, after swinging around to the

South, she moved down the stream, past the Statue of LIberty, and cut into the open sea.

"Goodbye, Old Girl," I called to the Goddess of Liberty, as we sailed by. "You'll have to look around the other way if

you want to see us again."

For at the moment I felt that we might circle the globe before returning to New York.

We were on our way to Europe!

To be continued...

Chapter I

Hollywood to Paris is copyrighted © by the Mary Pickford Foundation

and reprinted with the permission of the Mary Pickford Library.

Copyright © 2001, Diane MacIntyre, The Silents Majority On-Line Journal of Silent Film, at silentsmajority@visto.com. All rights reserved.

|